A debate on the value of an apology is attributed to Francisco de Quevedo and King Philip IV. The monarch argued that any offense was washed away by an apology. The writer claimed that a dishonest or poorly framed apology could be worse than the act for which forgiveness is sought. The king challenged Quevedo to offend him and find an apology that would be worse than the offense itself. As soon as the king turned around, the poet placed his hands on the king’s buttocks. Before recovering from the surprise, Philip IV heard the following words: “Forgive me, Lord, I thought you were the queen.”

I couldn’t stop thinking about this anecdote while sitting in front of the TV, watching some politician giving explanations on television about the pandemic. The level of mockery and frustration is so great that I have almost reduced my daily dose of news to zero, trying to channel my energy elsewhere. Quarantine also has its benefits. One of the problems you always face during vacations is how to intensely coexist with family for one or two weeks. After five or six weeks without leaving the house, you realize that the human being, in difficult situations, brings out the best and exceeds previously set resistance limits. You adapt to whatever comes much faster than you thought, and it seems to return to those first weeks of courtship where you become creative, understanding, thinking of the other above yourself. “Not too bad,” as my daughter would say! Time is better spent; you can read all those books you had in the pit lane and which the speed of everyday life continuously postponed. Right now, for example, I have five books scattered around the living room that I alternate according to my mood. “The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve” by Stephen Greenblatt, “The Son of the Century” by Antonio Scurati, about the rise of fascism to power in Italy, “Crash” by Adam Tooze about the 2008 crisis, “A Little History of Economics” by Niall Kishtainy (very easy to read and relatively short for those who want to get started in the world of economics), and some novel for light reading. You combine this with looking at stock charts, playing some chess, watching a series, the typical culinary learning, and a nightly family card game, and time passes without you noticing or missing having a dog.

It also makes us reflect on everything that is happening and, above all, how the world will be when we return. The financial world remains a curious one. The image of the week could be an instant recorded on CNBC. In the background, a large screen with a brutal headline: “The best week for the Dow Jones since 1938.” Below in small print: “More than 16 million Americans have lost their jobs in the last three weeks.” A piece of news that can be scandalous to the uninitiated but not so surprising to those who permanently “sing” the workings of financial markets. The gap between the real economic world and the financial matrix continues to expand. It comes with an interesting fact: Since 1990, the top 1% of Americans by wealth have bought $1.2 trillion in stocks and mutual funds, while the remaining 99% have sold a trillion dollars. Each new “saving” intervention by Central Banks immediately reflects in the pockets of the usual suspects. The Central Banks’ measures instantly spill over in the form of money printing and liquidity that always ends up going to financial assets, while fiscal measures take months to implement. While the American government will deliver $1,200 to each citizen, the 43,000 taxpayers earning more than a million dollars annually will each receive an average of $1.7 million in tax benefits in the package approved by Trump. If we recall the years before the Great Depression of 1929, we have similar examples: During Coolidge’s administration, Andrew Mellon served as Secretary of the Treasury, spending most of his working life authorizing tax cuts that conveniently increased his personal wealth. According to historian Arthur Schlesinger, with a single change in legislation, Mellon allowed a tax cut that saved him as much money as the entire population of Nebraska enjoyed. Mellon would request the IRS to send him the best workers to prepare his tax returns so that he would have to pay as little as possible.

In the face of a severe financial crisis threatening systemic interests, it has been revealed that we live in an era of large, unlimited governments, of large-scale executive measures, of interventionism that has much more in common with military operations than with governance subject to the law. This highlights an essential truth, whose denial had determined the entire development of economic policy since the 1970s. The foundations of the modern monetary system are irreducibly political. When we think in economic terms about some decisions made in high spheres, we are permanently wrong. The political and propaganda interests of power are above economic laws, and unfortunately, above the rest of the laws that govern their legal systems. And this conclusion can be drawn worldwide, regardless of the political sign of the ruler. Central Banks are operating outside their legal framework, and no one can say anything. The American Federal Reserve (which we must never forget is a private institution, whose main shareholders are the commercial banks themselves) is attributing things to itself for which it is not statutorily qualified. The phrase attributed to Machiavelli, which he did not write, “The end justifies the means” prevails above all. Always the urgent over the important. And since the transatlantic ship has set a course that seems unchangeable, fueled by debt and money printing, it seems that the only thing that can be done to overcome the wave coming our way is to double the fuel to the boilers. Nothing else matters. Just look at the statements of the FED governor of Cleveland, Loretta Mester: “The FED does not have to worry about moral hazard right now.” The harsh truth about the political history of Ben Bernanke’s global liquidity injection was that it involved handing out trillions of dollars in loans to a cabal of banks that had caused the crisis, to their shareholders, and to their executives with scandalous remuneration.

Regarding the market, there is little more to add. Investment banks keep changing their opinion every week and continue attributing to themselves the necromantic powers of knowing what will happen. They are always certain. Three weeks ago, we were going to hell, and now, everything is going to be fine. Is there anyone left who pays to receive these people’s reports? Our vision has not changed. We have no vision. The world has not changed in these two weeks, nor has the fog lifted. We only have the attempts of many governments to return to normal as if nothing had happened, but we do not know what effects it will have on the subsequent spread of the pandemic. Saying that the curve of infected people is decreasing when everyone is locked up at home is still a shot in the dark. The aid that governments are giving (mainly lines of credit and guarantees) will not prevent insolvency and closure of many businesses. Nor will it prevent a spike in bank delinquencies. In these two weeks, we have seen disparate things in the markets. While Europe, after a rebound prior to the United States, is slightly above three weeks ago, the recovery in American markets has been quite significant, recovering 61% of the drop in the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq returning to positive territory for the year. The bet on technology remains tremendous, while banks have returned to March lows, and oil in the USA is today marking levels below $15. Twenty-two percent of the capitalization of the American market is concentrated in just five technology companies. But despite all that “technology,” their main source of income is still the advertising market. It seems complicated that when many advertisers are small and medium-sized companies eager for positioning, who paid handsomely for it, are going through a survival crisis, these big companies can show themselves invulnerable despite the disappearance of many competitors, as may be the case for Amazon. The market is, despite the drops, at its highest valuation level of the year. I can understand that the results of a single year are only a part of a company’s valuation, but I am also deeply skeptical of many analyses that do not adjust future earnings, considering the situation as temporary and easily recoverable. Many things will not (cannot) be the same as before.

Every time there has been a crisis, it has been paid for in two ways, either with tax increases or with inflation. The measures being implemented will not come free. As an Indian sage says: “He who throws his filth into the river, the river awaits his return with thirst.”

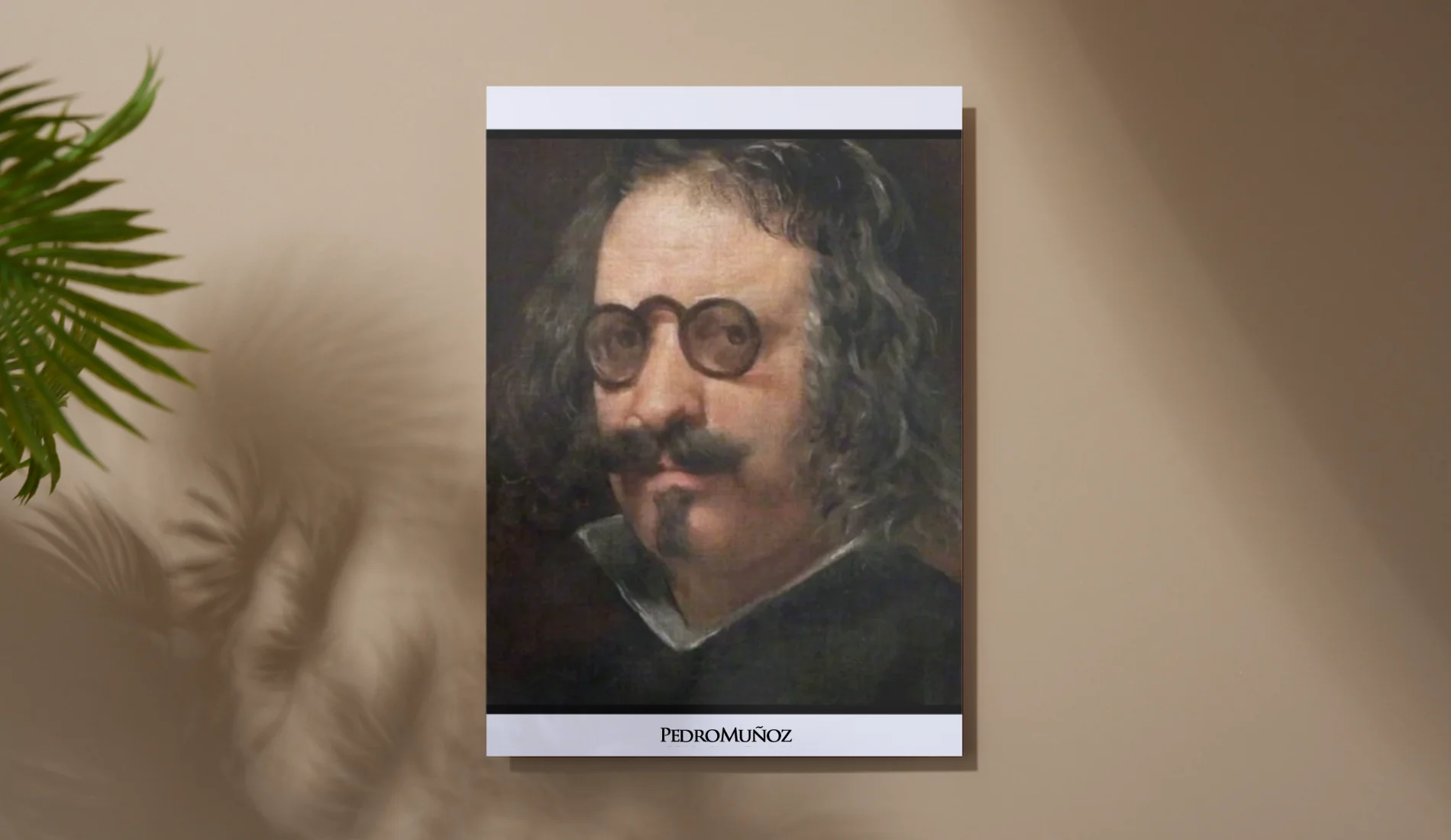

Pedro Muñoz